TODAY IN HISTORY | April 24rd

Welcome to another edition of Today In History, where we explore the history, conspiracies, and the mysteries that have shaped our world.

🐴🔥 First, we’re heading way back to 1184 B.C.—the date traditionally linked to the fall of Troy and the tale of the Trojan Horse. After a ten-year siege, the Greeks appeared to retreat, leaving behind a massive wooden horse as a “gift.” But hidden inside were elite soldiers, ready to open the gates from within. That night, Troy burned. Whether it’s myth, history, or somewhere in between, the story of the Trojan Horse remains one of the greatest deceptions in legend.

🎨👨🎨 Then, in 1503, Michelangelo began work on a series of sculptures of the Twelve Apostles. Commissioned for the Florence Cathedral, these statues were part of a larger project to celebrate the Church’s most iconic figures. Though the original statues were never completed, the designs reflect Michelangelo’s early genius and his growing influence in Renaissance art. This was the same year he started the David—not a bad year for a guy in his twenties.

Let’s dive into some history!🌎

TODAY’S TOPICS

1184 b.c. - The Trojan horse

1503 - Michelangelo’s 12 Apostles

Extras

Operation Parachute 🪂

Killer Rabbit’s 🔪

Dentist Street Entertainment 🦷

Aztec Earthquake 🦎

1184 b.c. The Trojan Horse

Around 1184 B.C., near the end of the Trojan War. The Greeks and the Trojans had been at war for like ten years, and it was just dragging on with no real progress. The Greeks couldn’t break into the city of Troy, and the Trojans weren’t budging either. That’s when this clever Greek guy, Odysseus, came up with a wild idea: build a giant wooden horse, hide soldiers inside it, and trick the Trojans into bringing it into the city.

Mykonos Vase: earliest depiction of the Trojan Horse

The Greeks made it look like they had finally given up and sailed away, leaving the horse behind as some kind of peace offering. The Trojans thought they’d won. They pulled the horse into the city as a trophy, thinking it was a gift or maybe a symbol of surrender. That night, while everyone in Troy was partying and celebrating, the Greek soldiers climbed out from inside the horse, opened the gates, and let the rest of the army—who had just been hiding nearby—sneak in.

It was total chaos. Troy got wrecked. The city was burned, people were killed or captured, and that was basically the end of the war. It became one of the most famous stories in history, and the phrase “beware of Greeks bearing gifts” came straight from this. Whether it actually happened exactly like that? Who knows. Most of what we know comes from later poems and myths, but it clearly struck a chord that lasted for thousands of years.

Depiction of Trojan Horse in Çanakkale, Turkey

Archaeologists think the real city of Troy was in modern-day Turkey, and there’s been some evidence of a big battle or destruction around that time. So something definitely went down—but the horse might’ve been more of a symbol or a trick of some kind, not a literal giant statue full of dudes. Still, the story is unforgettable either way.

🤖 Ai Depiction of Event

On To The Next Story!!!

1503 Michelangelo’s 12 Apostles

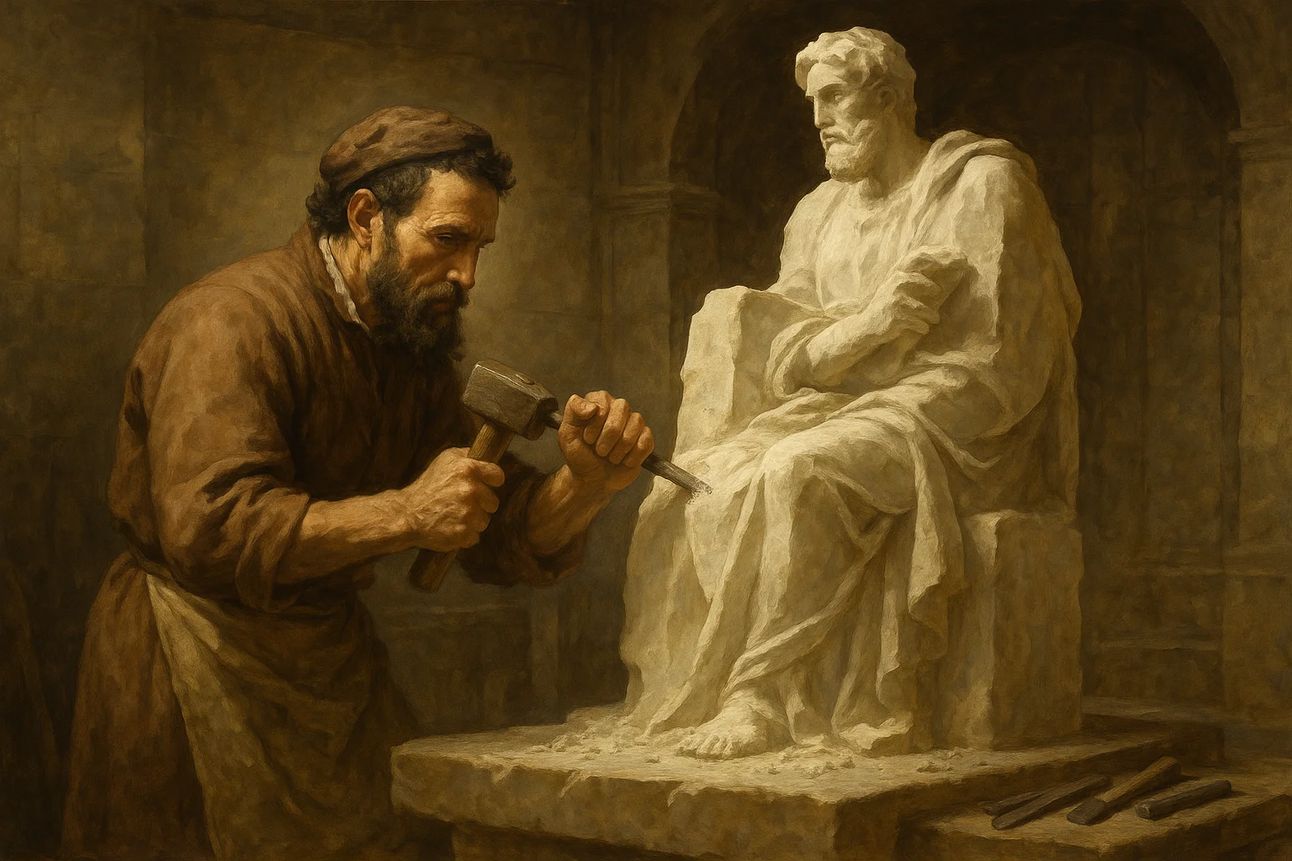

In 1503, Michelangelo was riding high—he was already famous in Florence, and people were lining up to get him working on their projects. The city had this big plan: they wanted him to carve twelve statues of the apostles for the inside of the Florence Cathedral. Big, bold marble statues, one for each of Jesus’s crew. But spoiler alert: the full project never got done.

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni

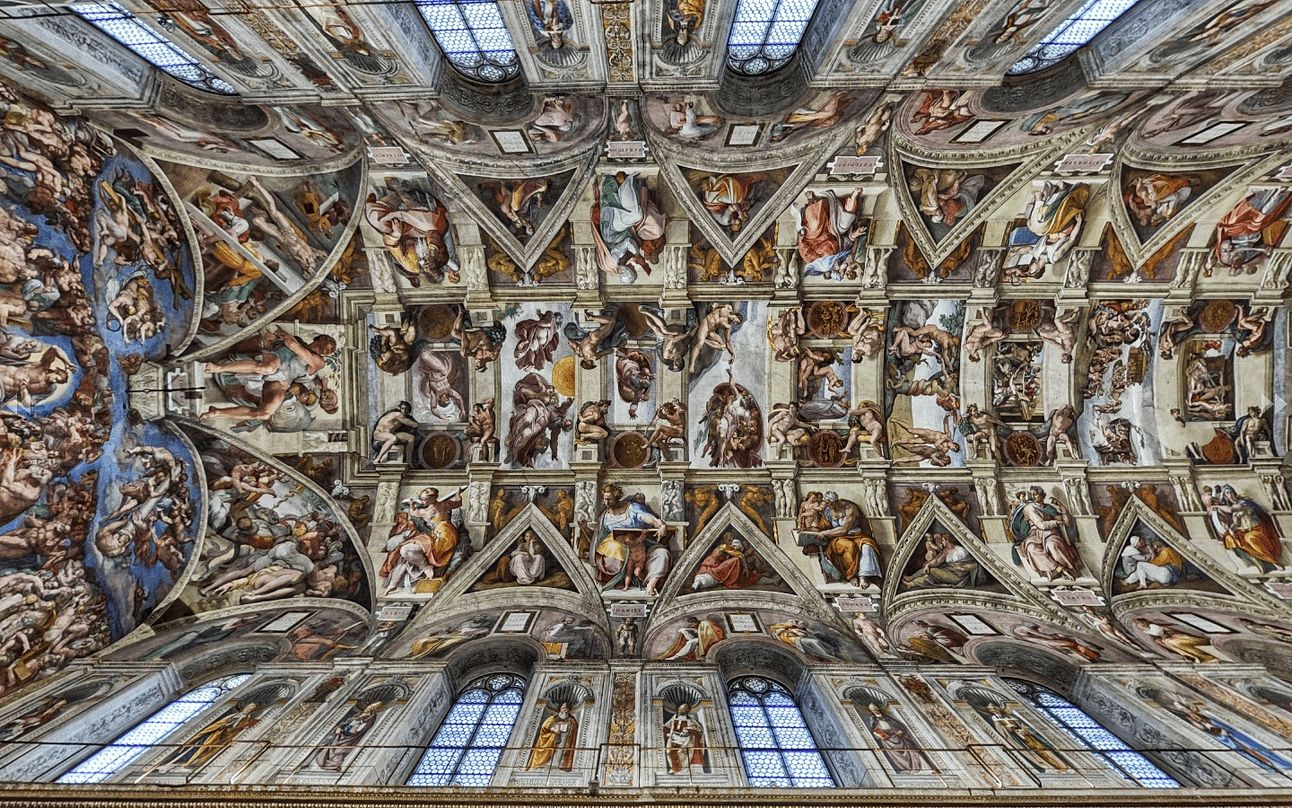

Michelangelo only got around to working on one of them—St. Matthew—and even that one wasn’t finished. It’s not that he didn’t care; he just had way too much on his plate. Around this time, he got pulled into working on the statue of David, and not long after, he’d be painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Plus, the political scene in Florence was getting messy, and stuff like funding and leadership kept changing. So the apostle project kind of got shelved.

The Sistine Chapel

That unfinished St. Matthew sculpture is still around today, actually—you can see it in Florence at the Accademia. It’s rough, like the figure is still fighting to break free from the marble. But that’s what’s cool about it. A lot of people think Michelangelo meant for it to look that way, kind of as a metaphor for the human soul or struggle. Whether that’s true or not, it’s still got that powerful, unfinished energy.

The unfinished sculpture of St. Matthew

So yeah, we never got the full twelve apostles from him, but even the one piece we do have gives us a glimpse into how he worked and what he was capable of. It’s a reminder that even the best artists don’t always finish what they start—but what they leave behind still makes an impact.

🤖 Ai Depiction of Event

Operation Titanic🪂

During World War II, on the night before D-Day (June 6, 1944), the Allies didn’t just send troops into Normandy — they also dropped a bunch of fake ones. As part of Operation Titanic, the U.S. and British forces dropped hundreds of dummy paratroopers, known as “Ruperts,” into enemy territory. These were stuffed figures, parachuted in to look like real soldiers from a distance. The goal? Confuse and distract German forces, making them think the real invasion was happening elsewhere. Some dummies even had explosives or noisemakers to simulate gunfire once they landed, just to sell the illusion harder. And it worked. Nazi commanders diverted troops away from real landing zones, giving Allied forces an edge. So yeah — the U.S. dropped scarecrow soldiers out of planes to outsmart Hitler. 🪂🧠🇺🇸.

Killer Rabbit’s🔪

If you’re ever just chilling and decide to crack open some early medieval manuscripts, among the saints, dragons, and monks, you might spot something...odd: rabbits wielding swords. Sometimes they’re chasing humans, sometimes beheading them, and sometimes just looking weirdly smug about it. These little bunnies show up mostly in the 13th–14th century illuminated manuscripts, especially in England and France. Known as “marginalia,” these drawings were like medieval doodles — where monks, for reasons still debated, decided to get very creative. So why killer rabbits? Possibly satire. They may have been visual jokes, flipping the script where prey turns predator, or moral lessons wrapped in absurdity. Or maybe monks were just... bored. Whatever the reason, it means that long before Monty Python made it famous, medieval scribes had already weaponized the bunny. 🐰🩸📖

Dentist Street Entertainment🦷

Before modern dentistry made things (mostly) painless, getting a tooth pulled was less of a private medical procedure and more of a public spectacle — complete with crowds, shouting, and sometimes music. In 18th and 19th century Europe, especially at markets and fairs, “tooth-drawers” would set up shop right on the street. They’d yank teeth from screaming patients while an assistant played music or cracked jokes to distract the crowd. Some even had costumes and banners — because nothing says "fun day out" like watching someone lose a molar. People gathered not just to get help, but to watch, laugh, cringe, and cheer. It was medicine meets theater, and if you were lucky, you left with one less tooth and a good story.🦷🎻👀

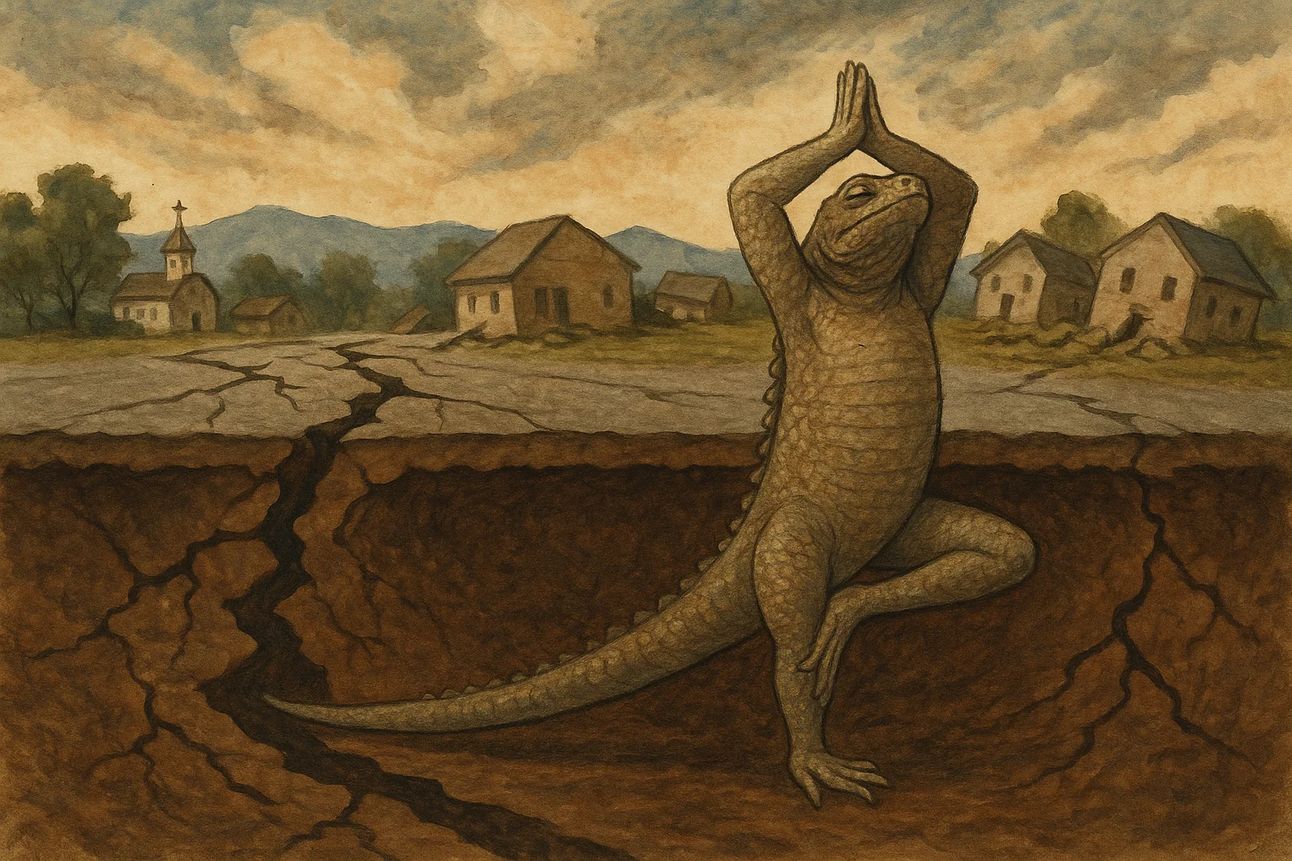

Aztec Earthquakes🦎

When the ground shook in Aztec mythology, it wasn’t tectonic plates—they believed it was a massive lizard-like creature shifting its weight or stretching beneath the earth. This wasn’t just any lizard—it was often tied to mythical earth monsters like Cipactli, a primordial crocodile-lizard hybrid that played a role in Aztec creation stories. According to some versions, when this cosmic beast moved or stretched, it caused earthquakes and other natural disturbances. Basically: Just a giant divine lizard doing yoga. It’s a reminder that for ancient cultures, myths were their science. 🦎🌋📖

Pop Quiz 📝

What historical figure was known to carry a pet rooster into battle for good luck? 🐓

Would You Rather?🧐

⚔️ Would you rather fight in the American Revolution or the French Revolution?

If you enjoy this edition of Today In History be sure to send it to a friend and force them to sign up because that’s what good friends do. Until next time, stay curious, question everything, and keep uncovering the mysteries of the past.